"When we graduated, it was the first year of the recession so there was no chance of getting a creative industries job," says Hillard. "You had to think about how you were going to earn money and I luckily got a job in chocolate."

She started out as an apprentice making chocolate for £4 an hour and spent five years honing her skills.

"It was all on you to learn it and it took me a while—chocolate is quite specific and precise," says Hillard. "I do love repetitive actions, which is all a part of art school, especially if you're doing something crafty. I challenged myself to get better and better."

Having mastered chocolate, Hillard turned her attention to ice cream and went to Italy to train at the Carpigiani Gelato University in Bologna.

"Ice cream turned out to be really similar in process to chocolate," she says. "All about temperatures, about crystal formations, how to balance fats and sugars, so I was like, 'Easy!'"

Less temperamental than chocolate, ice cream liberated Hillard to experiment.

"There's only a certain amount you can do in chocolate without it going wrong but ice cream was like a revelation because you can go really crazy without ruining it," she explains.

Hillard opened the milk bar more or less immediately after training, again driven by the need to earn a living.

"I had no real practise before opening in July 2013 because the equipment is really expensive and makes in bulk, so I just opened and practised as customers came in," she says. "It could have been terrible. It was quiet to begin with but then there was the [Edinburgh Fringe] Festival and it felt so busy because it was just me."

After six months, Hillard had made over 200 flavours of ice cream. Today, she has lost count of how many there are.

"It has all been practising on the public, which I think is the best way," says Hillard. "If you do white chocolate and black olive in summer, people will try it because they're eating so much ice cream, then they request it back."

True to the name of her cafe, all of Hillard's ice creams have milk at their base.

"I chose not to have any eggs in my ice cream, it's 80 percent milk, 10 percent whipping cream, then sugar—lots of it," she explains. "It's a milk ice cream: the cow is queen. We sell a glass of milk for 50 pence, which is really popular in summer. In Scotland people often drink milk with dinner—with mince and tatties."

Mary's Milk Bar keeps the ice cream flavours seasonal, an idea some customers can't get their heads around.

"The bane of my life is people coming in and asking for a strawberry milkshake in the winter," says Hillard. "I don't really want strawberries in December when there are lots of other things like apples, pears, and quinces. You can do flavours like mince pie and stollen and everything mulled and alcoholic."

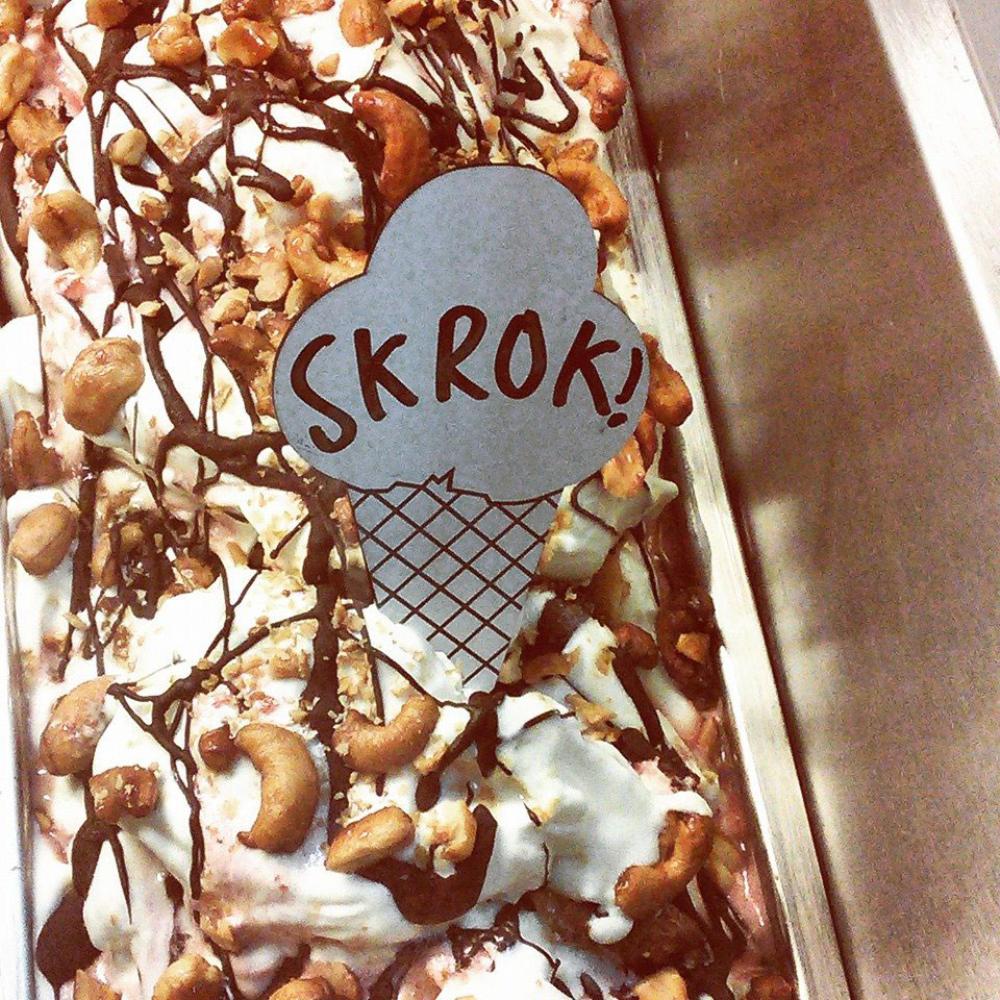

On my visit to the milk bar, there's a mysterious ice cream called "Skrok" in the freezer.

"A customer told us about Skrok and we were like, 'Are you sure? Because that sounds disgusting!'" explains Hillard. "She used to go to a tiny ice cream shop in Italy as a child and they only sold Skrok. It's a plain ice cream base, dark chocolate chip, a cherry ripple, pieces of cherry, and honey-roasted nuts."

As well as the such sweet creations, Hillard is not afraid of savoury flavours.

"We do quite a lot of cheesy ice creams," she says. "The strongest one we've done is Stilton and grape, which was surprisingly good. It was a beautiful shade of green but it would stink out the whole place when I was making it."

Not everything works, though.

"I made a Bloody Mary for Halloween and it was so disgusting," remembers Hillard. "The reason it was so disgusting is because it tasted like food, which is not what you want ice cream to taste of. It sold out though."

Collaboration with fellow independent food businesses is another important part of the milk bar. Twelve Triangles bakery, just up the road and run by other young, female artists, provide doughnuts on Fridays for Hillard's ice cream sandwiches and Glasgow's Bakery 47 deliver sourdough for her brown bread ice cream, as well as hot cross buns for Easter's ice cream sandwiches.

Hillard's downtime is spent visiting other milk bars—the few that are still left since government subsidies dried up and they fell out of fashion.

"Milk bars used to be in every town in the UK," she explains. "You had national ones that were government-funded, they would buy the milk from the farmer at a fair price, sell it to the milk bar at a loss, and they would produce cheap but nourishing food for industrial workers in big cities."

With no alcohol served in milk bars, they also became places for teenagers to go on dates unchaperoned.

"Milk bars were known for their teenage dates back in the day," says Hillard. "There would be booths, so there was quite a lot of canoodling over milk."

Looking towards the future, Hillard isn't thinking big.

"I don't want to make a lot of money, it's just having a job," she says. "I think that's quite a traditional way of running small businesses. Now it's trendy young men opening business to make bucks and then selling it on and doing something else and making money. It's just soulless. I wanted to be part of a community."

Source